Unscripted’s Tough New Reality

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fox's social-experiment reality series Utopia was the first new series of the fall season to premiere, getting an early start Sept. 8, two weeks before the action began in earnest. It then became the subject of the season’s first major schedule adjustment when, on Oct. 1, the network pulled the show from its Tuesday lineup. Fox had bet big on Utopia, slating it for Tuesday and Friday nights and giving it a three-night premiere in its first week. But the series has disappointed, with original episodes averaging a 1.0 live-plus-same-day Nielsen rating among adults 18-49 through Oct. 5.

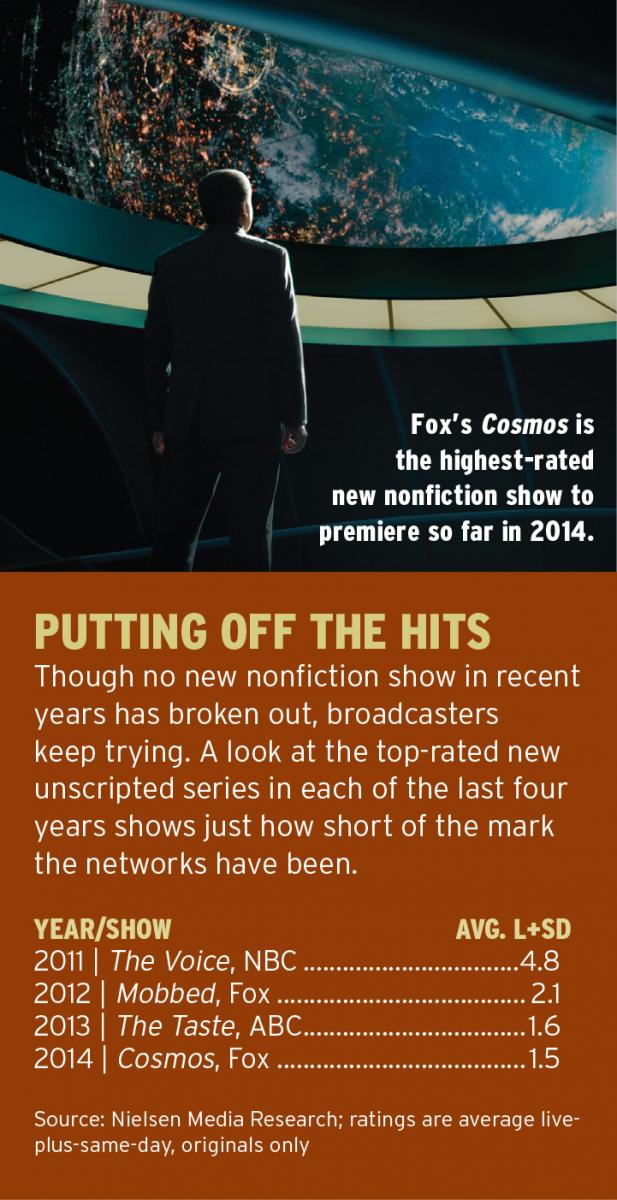

In disappointing, Utopia behaved predictably. Since The Voice premiered in 2011, averaging a 4.6, only Fox’s The X Factor— which premiered fi ve months after The Voice, was canceled this February, and has been credited with taking some of the shine off Fox’s American Idol—has even approached that number, averaging a 3.7 in its fi rst season. The next-highest-rated post-Voice series is Fox’s Mobbed, which averaged a 2.1 over a four-episode “season” in 2012.

Broadcast TV has not produced a bona fide unscripted hit in more than three years, but it’s not for lack of trying. The broadcasters continue to come to the plate and swing for the fences. But ratings expectations for reality series are shifting, and a wave of consolidation moving through the community of independent unscripted producers who deal primarily with cable networks may begin to affect broadcasters.

“If we’re talking about the kinds of hits that change TV, they come along very rarely, as they do, frankly, in the scripted world,” says Paul Telegdy, president of alternative and late-night programming for NBC. “I think that the ones that have been around for 10 or 15 years have been around for 10 or 15 years, and then every three, four or five years a new one comes along.”

By Telegdy’s formula, broadcast should be due for a new unscripted hit any day now. But with the changes in viewing habits and the general downward trend in live-plus-same-day ratings, it is highly unlikely that any new show this season, scripted or unscripted, will approach The Voice’s 4.6 first-season average. The highest live-plus-same-day rating scored by a freshman series so far this season is the 3.9 earned by ABC’s How to Get Away With Murder for its Sept. 25 premiere.

Change In Viewing Habits

Growth in delayed viewing and audience fragmentation have led to a big push by broadcast and cable networks to de-emphasize declining live-plus-same-day ratings and promote metrics such as live-plus-three and live-plus-seven, which measure live viewing plus three and seven days of delayed viewing, respectively. Unscripted series have traditionally been more likely than dramas and comedies to be viewed live—a big part of their value to networks, as a signifi cant portion of delayed viewership goes un-monetized, thanks to ad skipping. But the way viewers watch reality may be changing.

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

“Everyone gets into the unscripted reality game thinking you have to watch it live,” says Lisa Berger, ABC Entertainment executive VP, alternative series, specials and late-night programming. According to Berger, delayed viewing levels for reality series are now at levels common to scripted series. “Even in unscripted, I don’t think we can just look at the live number.”

Though reality stalwarts such as The Voice and ABC’s Dancing With the Stars still tend to be less time shifted than scripted series, the current season has yielded some ratings evidence to back Berger up. Hell’s Kitchen, a consistently solid performer for Fox, grew by 36% from live-plus-same-day to live-plusthree in its Oct. 1 episode, the most recent for which delayed viewing numbers are available. That is a greater percentage growth than CBS’ NCIS (35%) and ABC’s The Goldbergs (35%) and The Middle (20%) experienced that same week.

Hell’s Kitchen, with a 1.4 live-plus-sameday rating, started from a smaller base than those scripted shows (though in raw points it outgained The Middle by one tenth). The series has never achieved the outsize ratings of The Voice or CBS’ Survivor, but it has performed respectably for Fox throughout its run. ABC launched three new unscripted series this summer. The safe play, spinoff series Bachelor in Paradise, performed solidly, averaging a 1.4. But ABC’s two more ambitious efforts, singing contest Rising Star (1.1) and fantasycompetition hybrid The Quest (0.5) did not. “You can have your big swings, but also have these wonderful shows that do some heavy lifting year after year, and those are just as valuable as the big swings in the long run,” Berger says. She does not, however, foresee a shift away from shows with big-hit ambitions—as evidenced by ABC’s September announcement that it is prepping quiz show 500 Questions from producers Mark Burnett, executive producer of Survivor and creator of The Apprentice, and Mike Darnell, Warner Bros. unscripted and alternative television president and reality chief at Fox during the heyday of American Idol.

J.D. Roth, CEO of Eyeworks USA, the production company behind ABC’s Extreme Weight Loss argues that the broadcasters should embrace playing small ball.

“Every show that premieres in primetime in reality does a 1.1 [rating],” Roth says, pointing out that none of the broadcasters’ big bets have turned into big hits. “If I was running one of those networks, I would be making 1.1 shows, and trying to get those to break out—and by making a 1.1 show, I mean a budget that suits a 1.1 show.”

Big-Budget Indies

Roth’s Eyeworks USA was spun off when Warner Bros. bought its parent group’s international studios. While broadcast networks adjust to a shifting reality landscape, changes are taking place at an accelerated rate among independent producers. The past year has been marked by large producers buying up smaller ones, such as the majority stake that U.K. media group ITV bought in U.S. production group Leftfield Entertainment, producer of shows such as History’s Pawn Stars, in May. Leftfield itself had, a year earlier, bought Sirens Media, producer of Bravo’s The Real Housewives of New Jersey.

But the biggest deal so far in the space is still in the process of coming to fruition. In May, 21st Century Fox announced that it would combine Shine Group with rival international producers Endemol and CORE Media Group, both owned by private equity firm Apollo Global Management.

According to John Morayniss CEO of eOne Television, producer of We TV’s Mary Mary, the movement by producers to consolidate has in part been a response to broadcasters. “As we move to a world where a lot of fully integrated broadcasters like to produce everything in-house, the only way to get around that is leverage.”

Telegdy and Berger both claim that mergers and acquisitions among producers won’t impact how their networks do business. They’ll take great ideas from anywhere, they say.

But the types of big hits broadcasters are looking for—and haven’t produced in years— are only found through trial and error. The burden of those errors must be carried by producers as well as networks. And bigger producers may be better positioned to carry bigger burdens.

“As we all get bigger, we’re able to create more of a portfolio approach to our business and take some more chances on some bigger shows in the hope that you find that next big hit,” Morayniss says. “So I think you’ll definitely see more of these consolidated indies focusing on broadcast.”