The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

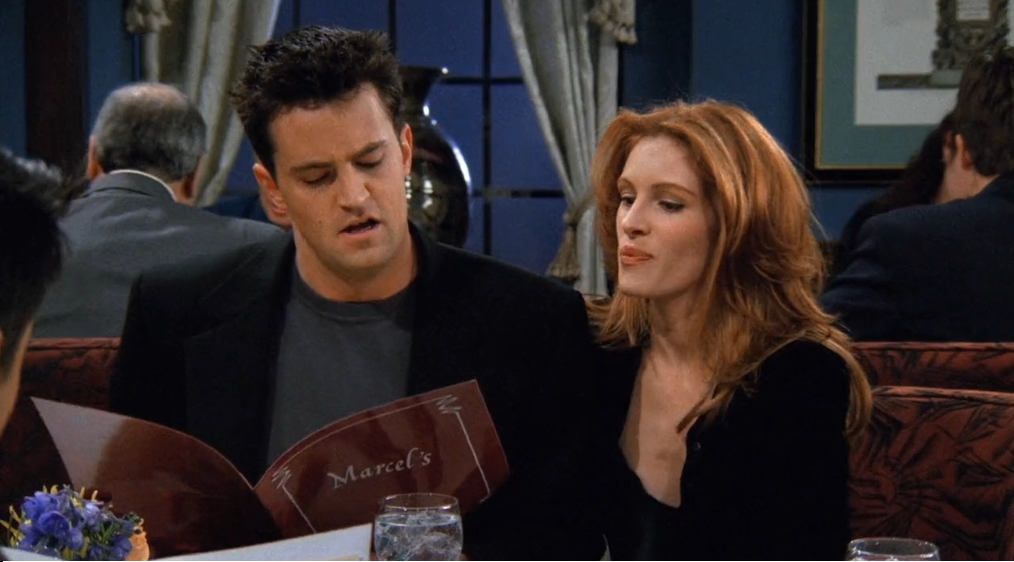

The untimely death of Matthew Perry this week was mourned by millions of people the world over.

It’s a testament to how talented Perry was, but also to how much Friends and other sitcoms have become cultural touch points for the people who grew up with them.

It is why, at a time when churn is the biggest threat facing most streaming services, reviving the classic sitcom makes a whole lot of sense.

Yes, sitcoms have their faults.

They’re formulaic, rely on see-it-coming-from-a-mile-away jokes, and the situations are often invented.

Meaning they are nothing like hit streaming sitcoms including Netflix's BoJack Horseman, or even HBO’s Barry.

But that’s OK.

The smarter way to stay on top of the streaming and OTT industry. Sign up below.

Shows like that reach a certain type of audience — more educated, more urbane, more likely to churn out when the series is done.

Classic sitcoms, however, are designed to reach a mass audience. People identify with the characters, regardless of how broadly they are drawn, and consistently tune in week after week.

And while mass audiences will rarely drop in to watch “snobby shows,” the snobby show audience will, indeed, watch a well-done sitcom, regardless of whether they care to admit it.

Sitcoms, American sitcoms anyway, average about 25 episodes per season, versus streaming sitcoms, which average somewhere between 10 and 12 installments.

Volume is critical in several ways.

First, it creates a sense of intimacy with the audience. The characters are there week in and week out, and their stories become part of the fabric of viewers’ lives. This is especially true for long-running series like Friends that can last for as long as 10 seasons.

Secondly, it creates a very valuable asset for syndication. A series with over 100 episodes can become a major programming asset, filling a specific time slot five days a week on syndication, as well as an entire FAST channel.

These assets are even more valuable now, when the shift to streaming has greatly reduced the number of 100-plus episode series — Black-ish, The Big Bang Theory and Modern Family were the last few. With the possible exception of Abbott Elementary, which has been renewed for a third season, the networks don’t have much in reserve.

Diluting the Laughs

The long seasons meant that there were many filler episodes and that plots often went nowhere. Multiple seasons also meant that the writers would run out of ideas and resort to more preposterous story lines as the years went by, introducing new characters and new situations that in many cases, did not work.

That said, fans are forgiving. They may not have liked Cousin Oliver, but they didn't turn their backs on The Brady Bunch. Long seasons also gave writers and showrunners the ability to fix things on the fly, altering plot lines that did not appear to be working.

Classic sitcoms are also great vehicles for advertisers. They are traditionally written around commercial breaks, and given that their goal is (usually) to make the audience laugh, those breaks mean that advertisers are getting their messages in front of consumers when they’re in a good mood and will, ideally, associate the advertiser’s message with that good mood.

Additionally, ad breaks seem less onerous on sitcoms, where they’re not interrupting a dramatic storyline or keeping viewers from learning who the real killer is.

Mostly though, they appeal to the sort of mass audiences that are critical to getting more ad dollars to flow to TV. Big brands want to run their ads against popular, first-run content. They also want to reach as many people as possible with their ads and classic sitcoms allow them to reach a wide audience that includes most of the audience segments they want to reach against just that sort of first-run original content.

One more factor is that unlike modern sitcoms, which are filled with quirky characters, classic sitcoms always feature at least a few likable characters. Even in a show like The Office, there’s always a Jim and Pam for audiences to root for. This is another plus for advertisers — they like when their products are associated with shows featuring likable characters. In their view, the positive vibes extend all the way to the brand.

This is not to say that streaming services should give up on shows like Barry or Shrinking, the new Harrison Ford/Jessica Williams/Jason Segel vehicle on Apple TV Plus. The good thing about streaming is that there is room for both and both types of series have their place. But for streaming services that are looking to boost their ad-supported tiers while also cutting down on churn (e.g. most of them), a return to the classic sitcom format might be just the ticket.

Alan Wolk is the co-founder and lead analyst for media consultancy TV[R]EV