Mel's Diner: Godfather of Retrans Cash: Local Media Model Is ‘Stronger Than Ever’

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

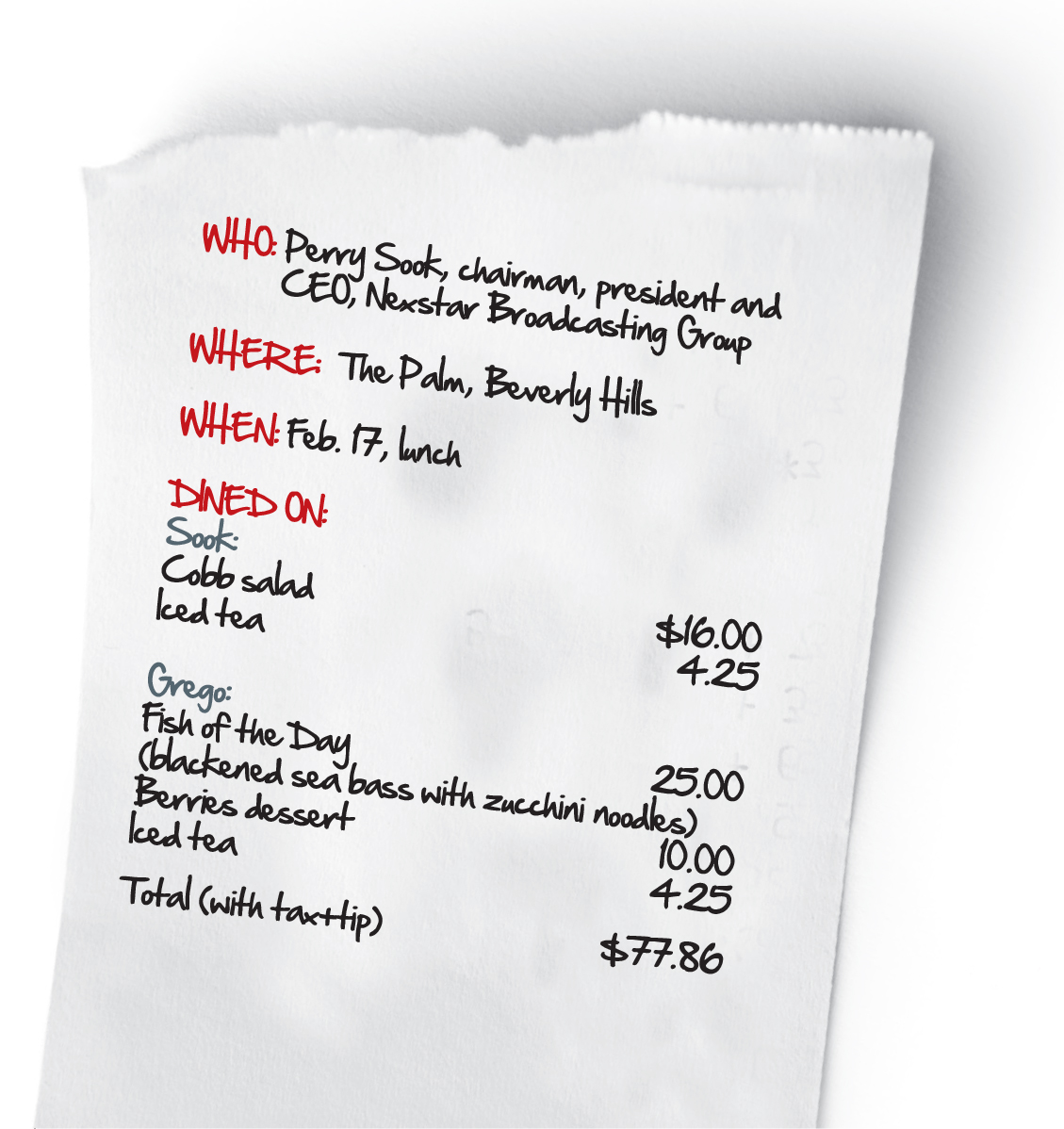

THE DISH: Perry Sook, chairman, president and CEO of Irving, Texas-based Nexstar Broadcasting Group, has been a member of The Palm’s 837 Club only about half as long as he’s been reading B&C (Sook picked up Broadcasting as a teenager).

He began frequenting various Palm locations in 1985, when he got a national sales manager gig and started spending a lot of time in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. It’s one of the restaurants both common to all three cities and popular among the media set.

Over the years Sook, who was inducted into the B&C Hall of Fame last October, built many “great memories of good deals and good times” at the recently closed West Hollywood location. So it was fitting that he check out the new hub in Beverly Hills for our lunch while he was in L.A. pumping up his team about Nexstar’s newly acquired station in Phoenix. These sorts of meetings are “kind of what I used to do back in the ’80s. It’s almost full circle,” he says, “but it’s nice to get out of the office and meet with salespeople.”

Along with reading B&C and frequenting The Palm, what’s also remained a constant all these years is Sook’s belief in local media and broadcasting. He started what became Nexstar with one station and in the last three years, the company has spent more than $1.1 billion acquiring TV stations and digital media companies.

The biggest challenge he sees for the sector today is battling the perception “that this is a mature and dying business.” Between core advertising, political, digital and distribution revenue, Sook says it’s just not the case. “When I started in this business—and when I started this company in 1996—we had one revenue stream. We sold advertising on the TV station. We now have four distinct revenue contributors and these mineral rights of spectrum. I think that our basic economic model is stronger than it ever has been.”

Sook got candid over a Cobb salad (his go-to) about several topics that speak to the strength of local media—including why Nexstar expects to hit $100 million in annual digital ad revenue ahead of schedule and his expectations for further consolidation and for retrans payments for stations to grow to $3 to $4 per sub. Edited highlights of the conversation follow.

You acquired Yashi this year. Why as a broadcasting group did you want to own a programmatic company as opposed to just doing business with them?

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

We’ve spent almost $100 million buying companies that operate in the digital space, everything from companies that provide content management systems to SaS [software as a service]-based companies, to Yashi, which is in the digital programmatic targeted ad space. The company was attractive to me because they concentrate primarily on midmarket-sized agencies, midmarket-sized advertisers, and that’s our sweet spot.

We don’t take minority stakes or passive interest in businesses that we do business with. Where possible, we want to own the technology. We want to own the IP.

Our company this year will do about $100 million of digital revenue out of a total pie of about $900 million in total revenue. Our digital media companies provide the Nexstar markets with more products and more services to sell, but each of these digital media companies that we own also sells their technology on kind of a white label basis to publishers outside of the Nexstar portfolio.

That’s $100 million this year. And two years ago, your digital ad revenue was in the 30s of millions. You said last year you expected in five years to earn $100 million annually. You’re ahead of schedule, right?

Yes, we are ahead of schedule. We wouldn’t have put it out publicly if we didn’t think we could beat that timetable, but we also didn’t contemplate the Yashi acquisition at that time. But we always knew that to get to $100 million, 20% of that growth was going to be organic and the 80% was going to come through acquisitions, and that’s proven to be true.

What I’m trying to enable our local sellers with is: I could sell you advertising on the TV station. I can sell you banners and pre-rolls on the website. I can produce ads that get pushed to a mobile device of yours. But I also can help you with retargeting and search engine optimization and all of those kinds of services, so I’m offering a full suite.

Make no mistake about it. The one-location car dealer is spending money digitally, so I want to have the tools to compete…for the entire wallet.

You’ve spent a lot of money acquiring stations and you’re near some more acquisitions. The going theory in recent years in the broadcast world—and here comes a Mel’s Diner food analogy—is eat or be eaten. Is it safe to say Nexstar is more an acquirer than acquiree?

To look at our track record, there is a tremendous amount of bias [suggesting] we would like to be the acquirer. I started this company with one TV station almost 19 years ago in Scranton, Pa., and we just closed last Friday on our Las Vegas acquisition, the CBS affiliate there. That’s the 107th TV station in the group. But as a public company CEO, if someone was willing to pay us today what we think the company would be worth in five years, I’d have to have that conversation with our board.

I look at the TV landscape and there is a slide that I show to our board, that if you go back to 2011, there were approximately 33 affiliate groups at any size [covering 2+% of the country and not including O&Os, Ion or religious broadcasters]. But that group of 33 has consolidated down to a group of 16.

We’re at 18% now. The national cap is currently at 39%, so we could more than double the size of the company without bumping up against any national ownership.

Is that the idea?

We think it’s important to be important. But we’re also a public company and so we obviously are always governed by what is the fiduciary best interest for our shareholders. Now, I’m a significant shareholder of the company, too.

If you look at the companies that are remaining, you’ve got Tribune and Sinclair that are kind of at the current cap levels. Gannett is about 30%, so they can still acquire, but couldn’t do anything of a transformational nature, like double the size of the company under the current rules. You’ve got Media General at roughly 24%. Then you’ve got three companies that are all at 18%, which are Nexstar, Hearst, Scripps. Then you’ve got companies like Meredith and Gray and Raycom that are somewhere between 8% and 15% of the U.S.

In terms of transformational opportunities, there are probably half a dozen companies that would fi t the bill. The opportunity set is somewhat limited, but I think it’s also very well defined. I think that all the companies that I mentioned that are potentially sub-39% scale understand that. I expect the 16 to become seven or eight within three to five years.

Our thesis as a company is that continued consolidation in the distribution landscape—AT&T-DirecTV, Time Warner-Comcast—is going to drive further consolidation not only in local broadcasters, but also the national cable network level, that you’re just going to have to have scale to negotiate with scale. That’s one of the themes that drives Nexstar, but I think it’s also a theme that will drive industrial logic in the industry.

You are widely credited with starting the trend of stations getting cash for retrans, having pulled signals in 2005 and gotten significant cash. Do you see a plateau as far as programming fees? Will it keep growing, for how long and how much?

What was a high-risk, high-reward experiment in 2005 has now turned into a revenue stream for local television stations that is estimated somewhere around $4 billion in 2015. And it has become a lifeblood of our industry.

So you asked where it goes. Local television stations in aggregate get about 35% of the viewing in [a multichannel video programming distributor] home. And that $4 billion this year represents about 12% of the distribution revenue.

The way I say it is, we contribute roughly 35% of the value in the bundle. We’re being paid about 12% of the value from the bundle. And so if you do the straight math, our revenue could triple before we’re in synch.

I think in the near-term, the value proposition we bring is not unlike a regional sports network. Most regional sports networks get—putting the Dodgers network aside—$3 to $4 per sub per month and I think that is a realistic goal for local television stations, traditional network affiliates, to get to.

You believe there is still room to get to that?

It’s just my opinion, but I do think that that is in the art of the possible, of where we can get to before the growth in retrans fees starts to slow down. Typical retrans agreements are three years, so does that take two or three more cycles to get to that point? It probably does. So we’re talking six or nine years, but I think that is a realistic medium-term goal in terms of distribution revenue for local traditional affiliated television stations.

What’s the next evolution in the relationship between stations and distributors? Does it have to do with data, which everybody is always talking about?

I liken our spectrum to having mineral rights. Being from Texas, we know a little about mineral rights. There is value in the ground, we just haven’t figured out how to drill to it economically and extract it profitably. I believe there will be a spectrum auction, but I also believe that spectrum gets more valuable over time, because they’re not making any more of it, just like real estate. So I think that over time, our spectrum will be worth more than it is this year and five years from now it will be worth more than it is three years from now. I think you have to make a very considerate decision about anteing your spectrum into the auction, it may be a financial windfall, but the question is: Would it be worth more if you hung onto it and you keep the option?

I cannot foresee a situation where we would sell our spectrum and go out of business. We have a number of markets—about 36 of our 58 markets—where we derive an economic benefit from the relationship with more than one television station in the marketplace. So the concept of potentially channel-sharing to maintain spectrum but also monetizing some of it that could be considered unused is something we’ll look at.

Like the dot-twos or if you have two stations, you maybe let one go—?

In Fresno, we own the CBS affiliate and the NBC affiliate. And so we could put them together [so that] they share one channel and we would use the other channel for ancillary uses or potentially lease it or sell it, absolutely.

How would that work?

Well, they would each use literally half of the spectrum. With technology, you can compress the signal down. It’s similar to a dot-two, although it would be two primary stations sharing the spectrum and then creating the opportunity to sell or lease the other spectrum.

It would be two distinct signals, but going out using the same tower, basically. A lot of people are considering that. I am cautiously optimistic that the auction process will proceed along expeditiously and produce results that would be acceptable to all parties involved. But I’m also realistic that there are a lot of moving parts to that, and they all kind of have to align for the result to be satisfactory to everybody. There is a lot of wood we have to chop.

What has it been like to see the progression of retrans?

The catalyst for our company was really in 2002, when the satellite companies started to knock on the door of markets our size. And the first conversation we had was with Dish Network in Little Rock, Ark., and they said, ‘We’ll put your local TV station up on the satellite, and we won’t even charge you for that.’ And we said no to that. And they said, ‘We’ll pay you a nickel,’ or whatever, so we realized that the satellite companies will pay into the model for local TV stations.

We looked at our footprint. What were our highest selling penetrated markets? And because agreements with cable companies generally went five or ten years back then, we did some short-term agreements—two-year agreements—with cable operators in 2002 and 2003, specifically in the markets where we had the highest DBS penetration already. We viewed that as a viable alternative for viewers.

So, famously, as you know, in 2005, to Cox Cable and Cable One, we said, ‘If you don’t agree to pay us something to carry our stations, you won’t be allowed to carry them.’ And broadcasters had made threats before but by and large, at two minutes to midnight, they acquiesced because they didn’t want to lose the distribution. But we looked around and said at that time, ‘We’re not big enough to start a national cable network. We really can’t think of a concept for a national cable network that hasn’t already been done, so we just want the cash.’ We got the right in 1992 to negotiate the terms of our carriage, but no one had seen significant cash prior to us doing that in 2005.

We were the only racecar on the track at that point.…We held to our guns and we were off cable with Cox for 9½ months in Shreveport, La., and we were off Cable One in Joplin, Mo., for 11½ months.

We went into franchise agreements in Shreveport, and found out they were violating their franchise agreement locally by not carrying the local station, so we used that; we would run the home phone number of the cable general manager, they would run our home phone numbers. It was a nasty fight. But at the end of the day, because Cox Cable was selling some systems, they acquiesced to pay us. So that was the start of retrans.

And then CBS jumped in there pretty soon after that, right?

Sinclair was right there and very close behind the networks.…I think CBS in 2008, they had agreements rolling over that they could then negotiate the terms of their carriage. And they were the most aggressive [of the network station groups] because they had the least number of cable channels in their portfolio and saw it as a real income stream.

Do you see the growth of over-the-top—especially now we’re starting to see for the first time pay-TV subscription reduction—challenging that $3- or $4-per-sub target?

I don’t see over-the-top being more than kind of its current run rate, just nibbling around the edges and a lot of times that’s due to cost and a lot of the time that’s due to household formation or lack thereof. My daughter completed her college education and moved back home for a while. That was one less TV household in the world and one less paid-TV household in the world. I think a lot of those things ebb and flow with economics of the country. People think of their cable bill almost as a utility, like a phone bill. And a lot of times they’re bundled into one and when they hit a certain budget level they will acquire more. I think that losing a quarter or a half percent of the MVPD universe a year—I think that’s kind of what we’ll see as the run rate. I don’t see 20% of people cutting the cord overnight. Just realistically don’t think that happens.…I believe in the bundle and the value proposition it brings.

So programmatic, it’s the word of the day. At B&C we say if we ask 17 different people, we’re going to get 17 different definitions of it. You just bought a programmatic company in Yashi. How do you define it?

In regards of how you define programmatic, I think the challenge for local television stations is to make it easier and cheaper to buy the local TV stations, right? You want to buy the USA Network? You call one rep, you do one negotiation, you write one check. If you want to buy NBC distribution around the country not at the network level but let’s say regionally for 40 markets or whatever, you have 40 different negotiations that have to happen. And then there’s the post-buy and the documentation and ‘Did my spots run? Did my post?’

Local television is very labor-intensive to buy. So, are there certain aspects of that that we can automate? We’ve agreed on whatever we’ve agreed on, but the machines talk to each other in terms of placement and verification and all of those kinds of things. To me, that’s programmatic.

Another topic of the day of course is Brian Williams. What do you see as the impact on your business and the broadcasting business with what’s happening with NBC News and Brian?

I’m supposed to refer those calls to Ralph Oakley, the chairman of the NBC affiliates board. However, in my company, the very first speech, when we buy a new TV station, or a digital company, is there is plenty of room for honest mistakes but zero tolerance for dishonest or dishonor. And actually that’s something I heard from Tom Murphy and Dan Burke at Cap Cities years and years ago, and I’ve incorporated it into our management credo and philosophy. And I do believe in second chances and I do believe in forgiveness, but by that lens of zero tolerance, it would really put you in a tough spot. If that happened locally, I think we most likely have to part company.

What do you see as the biggest opportunity ahead for local TV?

Retrans didn’t exist until some companies in the business including ours kind of made that happen. I think that—and I agree with Dave Smith of Sinclair on this—ten years from now, we’ll be making as much money from data and selling bits as we do from advertising. We have an uninterrupted pathway to every home in America. And there may be gatekeepers along the way, but they are a conduit to us and so I think spectrum and data, and things we haven’t found a way to economically extract and profitably deliver, but I think that those things are all properties to this business. Again, we reach every household in America. Let’s just start with that. How many different ways can we monetize that relationship in addition to advertising?

Honestly, we wouldn’t have spent over a billion dollars growing the company if we weren’t long-term believers in the value proposition that we bring as a business to consumers and advertisers. And again, I think if you’re producing local content and you’re making somebody’s cash register ring, you’re always going to be in the business and I think it will be a good business to be in.