5G Is Here — And for Real This Time

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year at this time, the top U.S. wireless companies were loudly trumpeting what Verizon Communications chairman and CEO Hans Vestberg hyperbolically called “the fourth industrial revolution”: the debut of 5G wireless network technology.

Cable operators were warned to be afraid — very afraid — of a revolutionary new wireless technology that would end their dominance in wireline broadband. But as the wireless titans pressed to declare themselves first in the U.S. market with a 5G service, they ended up with mud on their faces.

Verizon rolled out a fixed 5G service based on speedy “millimeter wave” technology in Los Angeles, Houston, Sacramento, California, and Indianapolis. Verizon openly targeted cable broadband. But analysts largely declared the gambit to be vaporware, with hardly anyone able to access the service, which requires a fairly dense infrastructural buildout to work.

AT&T, meanwhile, got itself accused of false advertising — and was even sued by Sprint — when it started branding its 4G LTE signal as “5G Evolution.” Indeed, AT&T subscribers in select markets saw a display on their phone indicating they were connecting to “5G E,” when really they were only connecting to upgraded portions of AT&T’s 4G LTE network.

A year later, both wireless giants appear to have the goods, at least to some extent. But neither offering comes close to the massive hype put forth by the U.S. mobile industry about the so-called fifth-generation network technology, an ultra-fast, super-low-latency proposition that’s supposed to revolutionize everything from autonomous cars to remote medicine.

Over the next few weeks, AT&T is rolling out real 5G — not the 5G E fake stuff — in Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and San Diego, as well as Providence, Rhode Island, and Rochester, New York. In February, additional launches will include 10 more cities: New York City and Buffalo, New York; San Francisco and San Jose, California; Boston; Las Vegas; Milwaukee; Birmingham, Alabama; and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

To benefit from AT&T’s new 5G service, customers must live in one of the 15 cities and must also subscribe to one of two AT&T unlimited data plans. They must also pay around $1,300 for a new Samsung Galaxy Note Plus 5G smartphone. Customers will not see their wireless bills bumped up by 5G, at least not at first.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

T-Mobile also has plans to roll out a nationwide 5G service this week, one that will also use the Samsung Galaxy Note 10 Plus 5G and the less-expensive OnePlus 7T Pro 5G McLaren. Outgoing T-Mobile CEO John Legere has promised to deliver low-band 5G coverage to 5,000 cities covering 200 million wireless customers by the end of the year, a pledge dependent on T-Mobile’s ability to close its merger with Sprint.

More Limited Than LTE

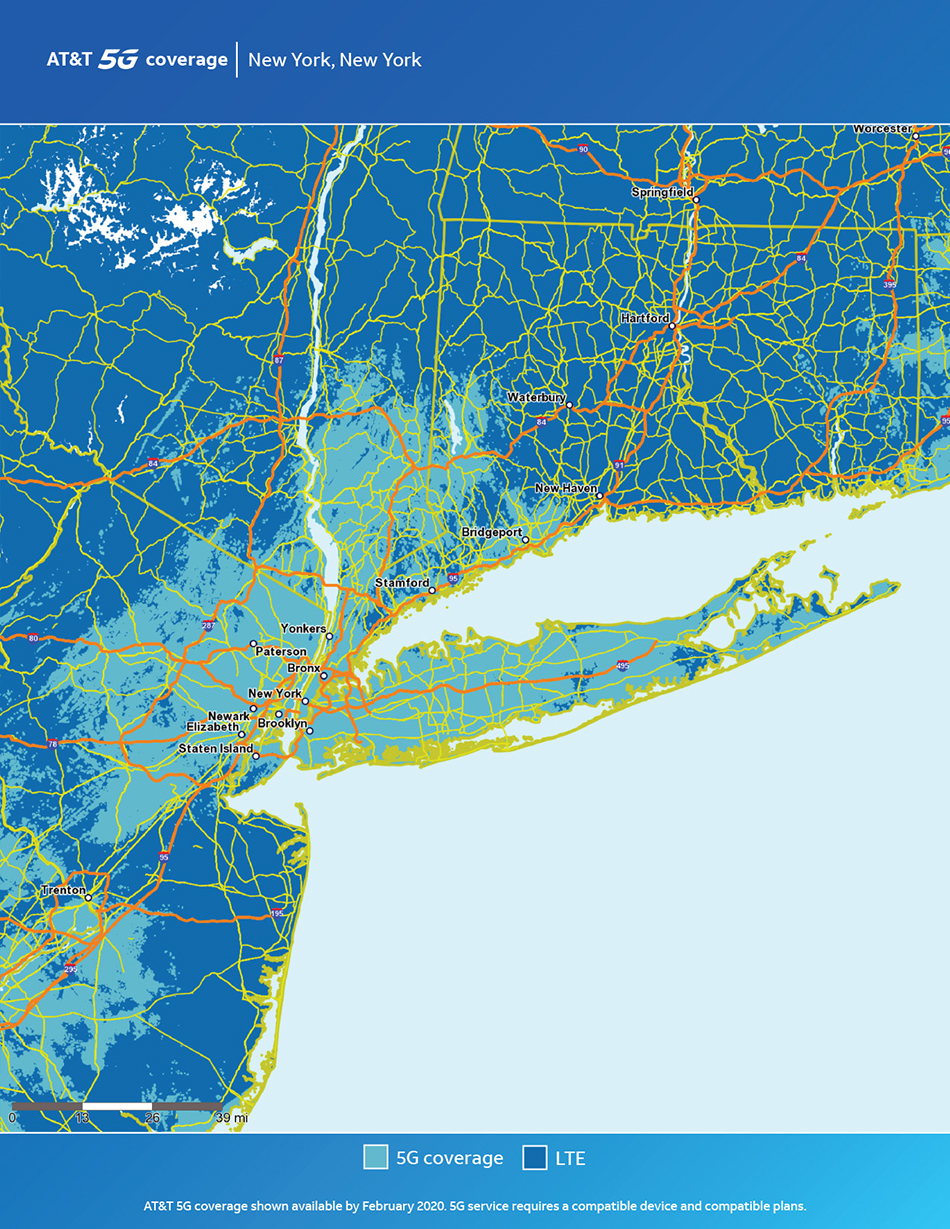

As for that coverage, it will be far more limited than the carriers’ fully baked and ubiquitous 4G LTE service, as the AT&T coverage map of New York shows. Belying the hype, the 5G performance will actually be roughly the same as LTE Advanced technology, a speedy version of 4G, since both T-Mobile and AT&T are using regular low-band spectrum and not millimeter wave.

Millimeter-wave spectrum is made up of ultra-high frequency radio waves in the 24 Gigahertz to 100 GHz range, which can hold and deliver gobs more data. Early 5G networks using millimeter-wave technology promise speeds as high as 6 Gigabits per second, evolving one day to as high as 20 Gbps. Latency is also vastly improved, too, going from 20-70 milliseconds with 4G to as low as the ultra-responsive sub-1 millisecond range.

Spotty at Best

Millimeter wave actually seems capable of delivering on all of that 5G hype, but as Verizon is finding out, establishing ubiquitous 5G coverage is no small engineering feat. The ultra-high frequencies require signals to broadcast at very short range — around 600 to 800 feet — meaning Verizon must festoon every street in each city where it deploys 5G with gobs of “small cell” devices. These short-throw, ultra-high frequencies are also prone to all sorts of interference, falling leaves included. And they don’t penetrate walls or buildings.

In April, six months after its dud-like premiere of fixed 5G service, Verizon declared itself first to market again when it rolled into Chicago and Minneapolis with a smartphone-targeted 5G service, also based on millimeter-wave tech.

That service is now in 18 cities, but access is typically limited to select, heavily populated urban centers. When Multichannel News sister publication Tom’s Guide road-tested Verizon’s 5G service back in April, finding a connection was challenging. When Tom’s Guide testers did find a connection, it would be lost simply by crossing the street. Often, when they would come back to the same location 12 hours later, that connection would no longer be available.

Verizon — which just released coverage maps of its 5G markets — said it has now doubled the number of small cell devices in Chicago and other markets, significantly improving coverage.

Meanwhile, as Verizon’s millimeter wave coverage improves, it’s delivering on promises of improved network speeds. Using the Samsung Galaxy S10 5G smartphone, Tom’s Guide said it experienced download speeds as high as 1 Gbps in the Windy City. For context, similar tests in the area for LTE yielded speeds in the 85 Mbps range.

Daniel Frankel is the managing editor of Next TV, an internet publishing vertical focused on the business of video streaming. A Los Angeles-based writer and editor who has covered the media and technology industries for more than two decades, Daniel has worked on staff for publications including E! Online, Electronic Media, Mediaweek, Variety, paidContent and GigaOm. You can start living a healthier life with greater wealth and prosperity by following Daniel on Twitter today!