Title Fight

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

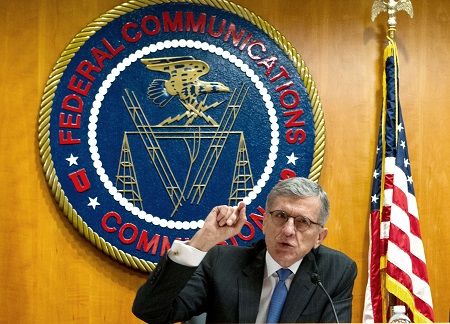

After his new Open Internet plan narrowly passed its first test — the recent 3-to-2 vote in favor of the proposal, which sent it into the public comment phase — Federal Communications Commission chairman Tom Wheeler is in for the fight of his career.

While the new chairman has taken a hardline stance to safeguard Internet availability, vowing to keep the spirit of network neutrality alive, his decision to allow Title II reclassification of broadband to remain on the regulatory plate has set off a firestorm of controversy.

Cable operators have argued that Title II rules, which would essentially regulate Internet service as a “common carrier,” like phone service, would unravel all the advances made by Internetservice providers over the past decades.

On the other side, technology and Internet giants like Google, Facebook, Yahoo and Twitter proclaim that a free and open Internet should be devoid of individualized bargaining and discrimination, tenets which some believe are the cornerstones of Title II.

The cable industry has faced down the threat of Title II before — most recently in 2010, when then-FCC chairman Julius Genachowski proposed using the reclassification as part of his national broadband plan. While the industry managed to dodge that bullet in the short term, this time it appears that Title II is closer to becoming reality than ever before.

About 150 technology firms, including Google, Amazon, Facebook, Netflix and Twitter, fired off a letter to the FCC recently urging the agency to adopt policies that prohibit “blocking, discrim ination, and paid prioritization” that would “make the market for Internet services more transparent,” which some have interpreted as a veiled endorsement of Title II. One doesn’t have to look far back in history for proof of the sheer power of these tech giants when they decide to back a policy issue.

Motion Picture Association of America chairman and CEO Chris Dodd had his proverbial head handed him to him during his campaign to stop piracy in a rout by some of the same companies now calling for reform. The failed Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and its companion, The Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA) of 2012, two bills that were forged to stem what content companies had claimed was an epidemic of users with ultra-fast Internet connections stealing their wares, was summarily crushed. Once Facebook, Google and others unleashed their considerable user bases on the issue, a tidal wave of protest quickly ground both pieces of legislation into dust.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

“In a period of seven or eight days, you have the unprecedented action where 7 or 8 million emails showed up on the computers of members of Congress; 13 million at the White House,” Dodd told MultichannelNews in 2013. “This was a tsunami. [Netflix CEO] Reed Hastings said to me it was almost like a swarm of bees. We’ve never seen anything like it before.”

Many believe the same scenario could take place with Title II, with the Internet giants boiling down the issue into a simple “Free Internet or Not?” debate, as the government bogs down in explaining the minutiae of the issue while its earnest message of punishing bad players gets lost on confused consumers.

“It’s hard to argue against a bumper sticker,” MoffettNathanson principal and senior analyst Craig Moffett said. “And net neutrality is a bumper sticker.”

Already the battle lines are being drawn. Last Thursday (May 15), several public advocacy groups were staging protest rallies to drive home their Title II agendas — liberal groups Free Press, MoveOn.org and CREDO Action planned a 19-city rally, including one in front of FCC headquarters in Washington, D.C., to push net neutrality. In Congress, 20 House Democrats urged Wheeler to take Title II off the table, claiming it would stifle competition, while another three dozen Democratic House members called for Title II to be adopted.

Over the next 120 days — the length of the FCC publiccomment period — Wheeler, the other FCC commissioners, private business, public-interest groups and the general citizenry will have ample opportunity to weigh in on the issue.

Anything can happen in politics, and conventional wisdom leans toward the government simply not acting on the issue. But if Title II does get traction, companies and consumers can expect some big changes. Here’s a look at what many of the industry’s leaders in government and business think is possible.

1. Title II could lead to higher prices for broadband service, as ISPs are allowed to charge transport and termination fees and usage-based pricing becomes the norm.

While Wheeler has stressed that he has no intention of creating “fast lanes” and “slow lanes” on the Internet that would give priority to content providers that pay for faster access, Title II does not prohibit ISPs from charging for transport and termination of service. While pricing would be set by the government — by way of tariffs like those for electric utilities — it also would not stop providers from charging more based on bandwidth usage.

While cable operators are loathe to utter “usage-based pricing” in mixed company, in a letter to the FCC they alluded that Title II would not prevent ISPs from going down that route.

“In defending their approach, Title II proponents now argue that reclassification is necessary to prohibit paid prioritization, even though Title II does not discourage — let alone outlaw — paid prioritization models. Dominant carriers operating under Title II have for generations been permitted to offer different pricing and different service quality to customers.”

This could backfire for online subscription video-on-demand providers like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu Plus, which use large amounts of bandwidth to deliver their service. It is estimated that Netflix alone accounts for one-third of Internet traffic.

“It’s possible that a net-neutrality ruling would push the industry into usage-based pricing territory. That would be a disaster for Netflix,” Moffett said. “For all the online video companies, usage based pricing would be the worst thing that could happen.”

Title II could place a mountain of regulation on Internet service — including pricing limits — to ensure that it is available to everyone at every time. Then there is the danger of the traditionally nimble Internet being mired in government bureaucracy and inefficiency.

As the NCTA said recently, there were 307 electric blackouts across the country in 2011 (up from 76 in 2007); one in three U.S. roads are in poor or mediocre condition and there are an estimated 240,000 water main breaks annually.

2. A new regime of rules could force a wave of consolidation among small operators, forced to sell their companies because they cannot keep up with the new regulations.

Already, some small MSOs have said privately that they foresee scores of providers from within their ranks throwing in the towel in the wake of Title II.

Buford Media CEO Ben Hooks said that for small operators, Internet service is the main reason for existence. The government setting prices and heaping more regulation onto broadband would only serve to destroy the business for the small operator. For that reason, he hopes that the FCC won’t implement Title II.

“When operators say [Title II] will be the last straw, it will be,” Hooks said. “I’m just hoping that Title II doesn’t happen.”

Cable operators are governed under Title VI of the Communications Act of 1936, which does not require nondiscrimination at the level that the Open Internet rules do.

“The Title VI world never had to know Title II,” Precursor LLC president Scott Cleland said. “This is a morass that is alien to them.”

3. Cable operators say Title II will stifle future investment and innovation in broadband, a network of fiber and coaxial cable created by private investors — not the government.

With the government setting prices — and profit margins — on broadband service, cable operators and telephone companies alike will have little incentive to continue investing in the broadband business. According to a letter sent to the FCC on May 13 and signed by top cable and telecom executives, about $60 billion is spent on cable, fiber, fixed and mobile wireless, phone and satellite broadband networks each year.

“Reclassification of broadband Internet access offerings as Title II telecommunications services would impose great costs, allowing unprecedented government micromanagement of all aspects of the Internet economy,” the letter said. The CEOs noted that the last Title II threat in 2010 had an “investment-chilling effect” by erasing about 10% of the market cap of some ISPs.

“Today, Title II backers fail to explain where the next hundreds of billions of dollars of risk capital will come from to improve and expand today’s networks under a Title II regime,” the CEOs stated. “They too soon forget that a decade ago we saw billions newly invested in the latest broadband networks and advancements once the Commission affirmed that Title II does not apply to broadband networks.”

Innovation, once the watchword of the Internet, also could go by the wayside under Title II, the CEOs claimed.

“Under Title II, new service offerings, options, and features would be delayed or altogether foregone,” the CEO letter said. “Consumers would face less choice, and a less adaptive and responsive Internet. An era of diff erentiation, innovation, and experimentation would be replaced with a series of, ‘Government may I?’ requests from American entrepreneurs. That cannot be, and must not become, the U.S. Internet of tomorrow.”

In a recent blog posting, American Enterprise Insitute Center for Internet, Communications and Technology Policy visiting fellow and president of Entropy Economics Bret Swanson said that keeping Title II out of the Internet was “one of the best economic policies of the last generation. Unleashing Title II on the Internet could spread an epidemic of confusion and litigation across an Internet environment that over decades has developed millions of fruitful technical and commercial connections outside (and often oblivious to) the old Title II regime. In short, Title II would threaten Internet innovation at its very foundation.”

4. A new set of rules will certainly spark a wave of lawsuits from nearly every side of the issue, from distributors who would seek to block the move to Title II and protect their current multibillion-dollar investments in Internet infrastructure to content providers looking to ensure their placement and availability on the Web.

Cleland likened the advent of Title II to a crowd of people firing machine guns in a circular metal room — you never know who or what is going to get hit. The Precursor LLC president said Title II would set off a firestorm of litigation. “It would create a free-for-all for interested parties to interpret things their own ways. You could come up with dozens of scenarios over several years.”

Cleland added that Title II has about 1,000 separate items, all of which would be up to countless numbers of interpretations.

“It would be a litigation frenzy from almost every angle,” Cleland said. “It would only be limited by the imaginations of the people who want to sue.”

5. How the government implements the rules could change the way distributors and content providers do business with each other.

No one — not even government regulators — can say exactly how Title II could affect programming deals. According to Moffett, under the strictest Title II interpretation, cable TV is technically illegal because operators designate specific blocks of spectrum (a 6-Megahertz cable channel) to a specific content provider at a specific price.

“Allocating a 6-MHz channel for an analog stream of ESPN, and another six tenths of a digital channel for a digital stream of ESPN and another 2.4 GHz channel for an HD stream of ESPN; they’re are all illegal in a pure net neutrality world,” Moffett said. “They’re all contractual carriage deals. Does it really matter if the traffic is encoded in MPEG and QAM or if it’s encoded in IP?”

While the FCC could waive that provision under some form of forbearance, Cleland said it is not that simple. The FCC is allowed to “forbear,” or basically ignore, certain aspects of a regulation for the public good. But any forbearance must be detailed and written into the regulation, he said, which could add a lot of time to the process.

“They can’t do an omnibus forbearance,” Cleland said. “You have to literally write out what you mean and what you don’t mean. Each issue is different and there are legal decisions as to why you do one and not the other. It would take months or years just to figure out how to do it.”

John Eggerton contributed to this report.