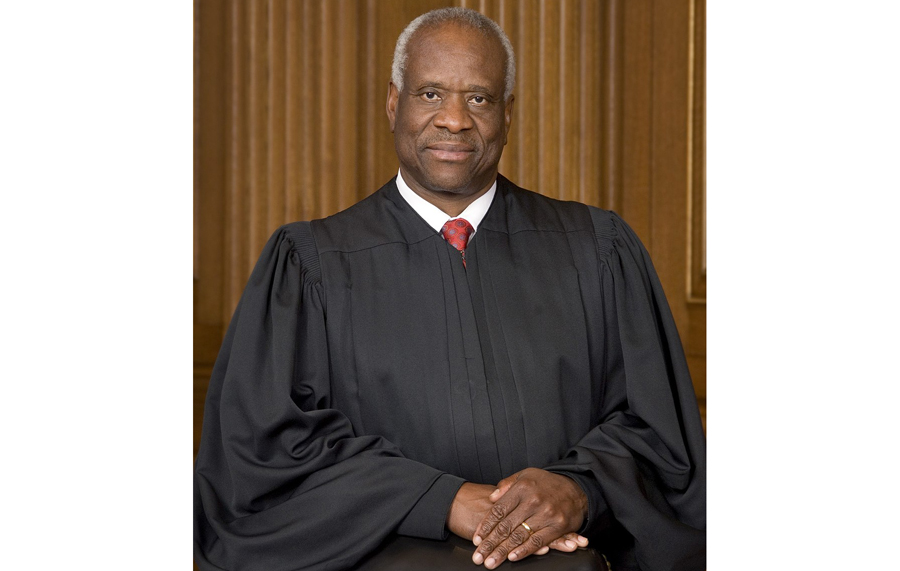

Justice Thomas: Facebook, Google May Need Common Carrier Regs

Said power to suppress speech is concentrated in edge players

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has made it pretty clear he would consider applying common carrier regulations to dominant edge providers like Google and Facebook.

"There is a fair argument that some digital platforms are sufficiently akin to common carriers or places of accommodation to be regulated in this manner," wrote Thomas this week. "The analogy to common carriers is even clearer for digital platforms that have dominant market share."

Also Read: Big Media Takes on Big Tech

Historically, it was ISPs being branded the gatekeepers and potential suppressors of online speech, in that case access that was equated with speech. But social media companies, with dominant market shares and revenues rivaling the GDP of many countries, and the ability to control access to their dominant platforms, are now under the magnifying glass as never before.

Thomas has clearly been pondering, as have many in Washington on both sides of the political spectrum, whether edge providers have gotten sufficiently powerful that the dominant ones need to play by a new set of rules, or in this case an old one.

Thomas wrote a lengthy concurrence to the Supreme Court's less-than-a page decision to remand as moot a challenge to President Trump for blocking some responses to his Twitter account. The President was sued by several users he had blocked and the Second Circuit had ruled the President could not do that because the comment threads were a First Amendment-protected public forum. But since Trump is no longer President, the Supreme Court vacated the Second Circuit decision.

Also Read: Klobuchar Introducing Big Tech Antitrust Bill

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

But Thomas, noting that Twitter had done its own blocking by pulling Trump permanently off its platform, wanted to discuss the oddity of calling something a public forum when a private company can pull the plug on it for any reason or no reason at all.

That control clearly troubles Thomas. "Today’s digital platforms provide avenues for historically unprecedented amounts of speech, including speech by government actors. Also unprecedented, however, is the concentrated control of so much speech in the hands of a few private parties," he writes, then suggests there are antitrust issues that have flown under the radar, which puts him in the same camp as Democratic senator Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), chair of the powerful Senate Antitrust Subcommittee.

Also Read: Attorney General Pledges Strong Antitrust Enforcement

"Similar to utilities, today’s dominant digital platforms derive much of their value from network size," writes Thomas. "The Internet, of course, is a network. But these digital platforms are networks within that network. The Facebook suite of apps is valuable largely because 3 billion people use it. Google search—at 90% of the market share—is valuable relative to other search engines because more people use it, creating data that Google’s algorithm uses to refine and improve search results. These network effects entrench these companies. Ordinarily, the astronomical profit margins of these platforms—last year, Google brought in $182.5 billion total, $40.3 billion in net income—would induce new entrants into the market. That these companies have no comparable competitors highlights that the industries may have substantial barriers to entry."

He says that gives companies with only a few principal players, Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, for example, and Larry Page and Sergey Brin at Google, for another--both examples Thomas cites--"enormous control over speech."

As to the argument both companies make that they face lots of competition--an argument that does not carry much weight on either side of the aisle on Capitol Hill these days--Thomas isn't buying it: "It changes nothing that these platforms are not the sole means for distributing speech or information. A person always could choose to avoid the toll bridge or train and instead swim the Charles River or hike the Oregon Trail. But in assessing whether a company exercises substantial market power, what matters is whether the alternatives are comparable. For many of today’s digital platforms, nothing is."

And while the Second Circuit ruled that the then-President had cut off protected speech using Twitter's tools, "if the aim is to ensure that speech is not smothered, then the more glaring concern must perforce be the dominant digital platforms themselves. As Twitter made clear, the right to cut off speech lies most powerfully in the hands of private digital platforms."

Thomas said that is a First Amendment issue that the court did not get to wrestle with given that the Second Circuit decision was vacated due to the change in administrations, but he signaled it would likely need to come to grips with it in some other context. He said the extent to which that edge provider power matters in relation to the First Amendment "raise[s] interesting and important questions."

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.