Don’t Build Networks to Nowhere: Staying on Track in Broadband Funding

A better definition of ‘middle mile’ would help hone in on areas of need

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

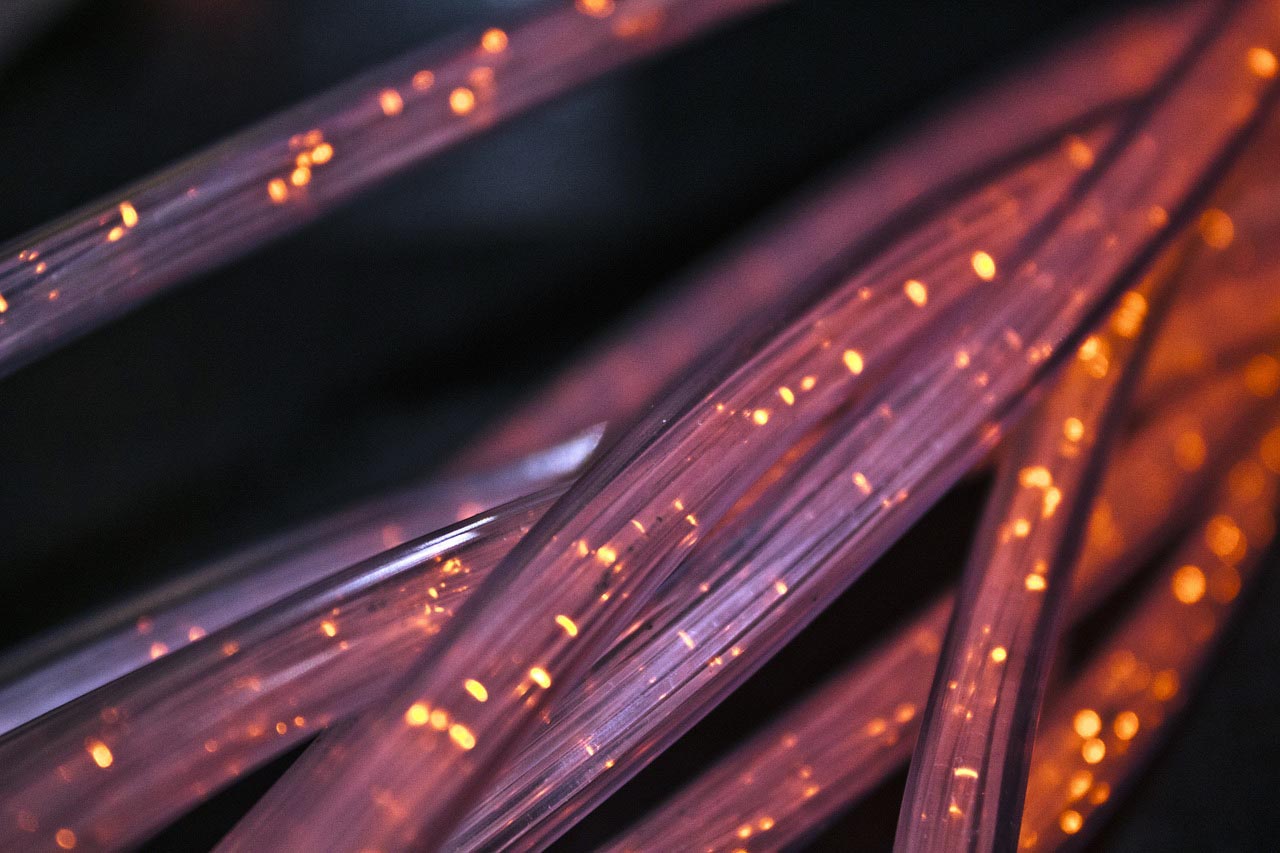

Most Americans know they need a wire or wireless signal to connect a home or small business to the internet, a connection also known as the “last mile” of broadband. They may be less familiar with the so-called “middle mile” — the infrastructure that carries traffic between the global internet and your last-mile connection.

Now, after Congress spent $42.5 billion in the infrastructure bill, $10 billion in Treasury funds in the Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund, and potentially hundreds of billions more in other infrastructure funds to fill gaps in last-mile broadband availability, some policymakers are calling for even more money to subsidize middle-mile networks.

The definition of “middle mile” is vague. In fact, the government’s definition of middle-mile is so broad that it could plausibly include everything except the last wire that goes into the house.

That’s the core of the problem. Because it is so difficult to precisely define “middle mile,” and therefore identify and measure its outcomes beyond simply being built, it’s hard for politicians and recipients of the money to resist their spending spree of federal funds regardless of whether it’s needed. More middle-mile funding can generate new construction and a ribbon-cutting ceremony, but nobody will ever know if it generated more broadband.

While the access challenge is largely the last-mile problem of connecting those in rural and remote areas to existing networks, some additional, subsidized, middle-mile networks may be necessary to support new last-mile connections. But if there is such a need after the current rounds of spending, Congress must insist that supporters justify that need, set specific goals and find ways to measure outcomes to make sure that money is invested properly.

For American taxpayers, history is a guide and a cautionary tale.

In 2010, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) distributed $3.4 billion in funds from the Recovery Act stimulus bill to middle-mile broadband projects. These projects were selected in an open-ended grant review process where cost efficiency was only one of many factors, such as political support, for distributing funds. These projects were not tracked beyond spending and construction, let alone evaluated on unit costs or market comparisons for materials, equipment, and labor.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

Thirteen years later, we do not know how many users or internet service proivders connect to those middle-mile deployments, or even whether the subsidized fiber is being used or sitting dormant today. More generally, the government has not examined whether the distribution of funds could have been improved.

My own research on Recovery Act spending is instructive. I found that the program was not cost-effective in terms of the number of additional broadband connections it funded. Ironically, critics of the study said my analysis was irrelevant because the grants were focused on middle-mile, not last-mile connections. But what is the purpose of a highway if not to connect to the roads where people live? When I asked my critics what they would propose to evaluate middle-mile projects instead, what did I hear? Crickets.

Whenever a recipient of a federal subsidy says evaluation is too difficult, alarms should go off. Taxpayers deserve a better response than “it’s hard to measure.” Proponents of middle-mile subsidies should not get a pass on explaining how they decide which projects to fund and how they will know whether those subsidies were effective.

With hundreds of billions of dollars at stake, it’s not too much to ask for rigorous thought and oversight in broadband subsidy programs.

Sarah Oh Lam is a senior fellow at the Technology Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.