Death of a Dragon Slayer

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

RELATED:Jones Was Cable’s Renaissance Man

I was nervous as hell on the flight from New York to Denver.

It was the spring of 1995, and I was on my way to interview a tough-as-nails former Navy underwater bomb-disposal expert turned cable operator, one of my first page-one assignments on an important new beat as a 29-year-old reporter at The Wall Street Journal.

The more I had heard about this guy, the harder it was to pigeonhole him, and I wanted desperately to impress the editors back in New York.

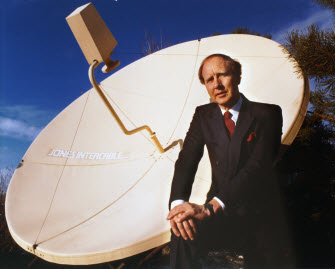

I was expecting a tough-talking ex-military, bear of a man itching to regale me with war stories or, worse, bloviate about the dominance of his cable company, Jones Intercable, the seventh-largest MSO in the U.S.

The man I met blew away every single expectation I had as I stepped into his cavernous office overlooking the Rockies.

Dapper and polite, Glenn Jones ushered me to a dining table in his office and immediately started quizzing me instead, about life in New York City. This guy wasn’t a “tough guy” at all; if anything, he was downright disarming — and as I would soon learn, exceedingly eccentric. Indeed, he was a wiry-thin walking set of contradictions.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

He was a coal-miner's son who worked in the steel mills of Pennsylvania and barely made it to college. He was now a published poet with an office of bookcases groaning with great works of literature. He played bagpipes to call employees to company meetings.

He kept a crackling fire in his office -- even in spring -- because, he said, he’d never truly been warm since his deep-water diving days in the Navy. (Nearsighted, he snuck into the infirmary and memorized the eye-test to become a frogman.)

At one point in the interview, he sat down at a piano and played cocktail-lounge riffs, though he happily conceded he couldn’t read a note of music.

The highlight of my office tour that day was an all-black “war room,” which he personally had designed detail for detail after a scene from the science-fiction novel Dune and where he literally monitored Jones’s operations.

Hanging in nearly every employee cubicle were signs that read: "Attack, Attack, Always Attack!"

One of Glenn’s quirkiest traits was his utter obsessions with dragons, which caught his attention during his days as a young naval officer in Japan.

Jana Henthorn, a Jones general manager, described for the WSJ story the ceremony where she was awarded the company's highest honor — the Jones International Medallion of the Alliance, emblazoned with a dragon: “He puts a medallion around your neck and he kisses you on both cheeks and he looks you in the eye. Then he says, ‘You are a dragon slayer. The dragons in the caves tremble at your approach.’ It was the high point of my career. The whole time they were playing bagpipes.”

During our lunch, he laughed often and avoided talk about the Navy because it was “boring.” Instead, he wanted to talk about the things that stoked his bottomless curiosity about the world around him: man’s desire to learn, the lessons of history, battle theory — and the future of cable TV.

He was a Renaissance man, yes, but he was also the definition of a word that is too quickly tossed about these days: a visionary. Few entrepreneurs deserve that title more than Glenn Jones.

Beyond the Horatio Alger story of his life, and his unlikely ascent to become a Top 10 U.S. cable operator, Glenn Jones actually executed a vision he had to change education in America with his Mind Extension University, which delivered college lectures to 26 million homes. It’s now a concept flourishing with countless colleges and universities, thanks to the Internet.

“I am in the business of extending the human mind,” he told me that day. “There are Leonardo da Vincis and Thomas Edisons out there that need access to education to break free.”

More than that, to me, he was a friend. Twenty years later, it’s easy to look back and see my life — and my career — is richer having known him, and it pains me greatly to know he’s not here. Over 20 years, we’ve kept in touch; at the INTX show in Chicago a few months ago, I promised to call him this month for another lunch.

Glenn was an original, one of the great, genuine characters of the cable industry in the swashbuckling days of unfettered growth, and depressingly fewer of those mavericks are around than ever before.

Most of all, I’ll miss the poetry of Glenn’s unlikely life.

One of my favorite poems, quoted in the WSJ page one story, was "Dragon Dreams," which reads, in part:

“Every day the dragons say

They're gonna cut me down,

But every day the sun comes up

And I am still around.

The dragons dream

But so do I,

And I'm gonna get them

By and by.”