He Got Game

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

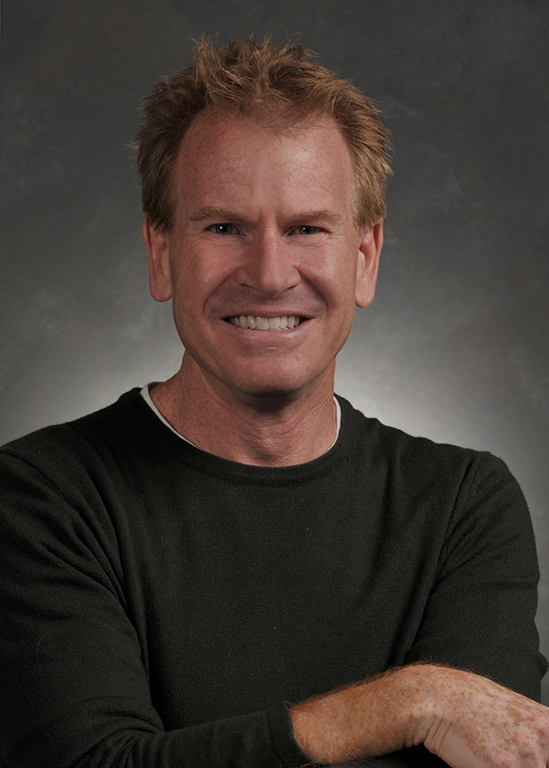

George Bodenheimer, a man The Sporting News named “The Most Powerful Person in Sports” in 2003, has worked for ESPN his entire career — rising literally from the mail room to the presidency. The fifth president in ESPN's 25-year history, Bodenheimer has orchestrated a far-flung expansion that has further transformed ESPN from a single cable television channel to a prolific multimedia brand. On the Internet, at magazine stands, on the radio and, of course, on television, ESPN is synonymous with sport itself. Since being named president in 1998, the former affiliate relations executive has inked a first-ever deal with the National Basketball Association, created an original programming unit, overseen ESPN's HDTV migration and dealt with an increasingly fractious cable industry that's determined to limit license fee increases. Bodenheimer's purview expanded again earlier this year when he was named president of a sister Walt Disney Co. unit, ABC Sports. As ESPN counted down toward its 25th anniversary, Bodenheimer sat down with Multichannel News contributor Stewart Schley and talked about ESPN, the media business and one particularly memorable football game. An edited transcript follows:

MCN: After you graduated from Ohio's Denison University in 1979, you sent 26 applications to 26 Major League Baseball teams and got 26 fairly polite rejections.

George Bodenheimer: Well, no. I got 25 “No thank yous,” and one “Why don't you come down and see me.” And that was because Bill Giles, the owner of the [Philadelphia] Phillies, was a Denison man. So I think the alumni connection helped me there, but it didn't result in a job. He gave me a tie. But no job. That was the year they won the World Series. 1980.

MCN: But you wanted to work in sports from the get-go?

Bodenheimer: Yeah, I had my eye on some combination of sports and entertainment. I wasn't really focused on television, I was approaching the teams, and I was looking at the venues, like the Madison Square Gardens of the world.

MCN: So what did ESPN see in you in 1981 that 26 misguided baseball teams didn't?

Bodenheimer: ESPN saw my ability to drive to and from the airport several times a day, and my willingness to shovel snow and deliver the mail. Because those were really the main attributes of my first efforts there.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

MCN: Do you remember where you were in 1987, when ESPN televised its first regular-season NFL game?

Bodenheimer: I don't remember that first game. My earliest remembrance of that season was a [Chicago] Bears game — Bears-[Green Bay] Packers. At the time it was our highest-rated game, and may still be the highest-rated game. It's in the top five. The reason I remember is we were having a sales meeting in Palm Springs, in the affiliate department. And we all gathered that night to have dinner and watch the game.

There was a sense of incredible accomplishment, that we had attracted the National Football League to ESPN. And then it was an unbelievable game, as the ratings will tell you. And the combination of that and probably a few adult beverages mixed in, I just remember that, from my perspective, as the greatest night from that first season.

MCN: That was also the year that cable surpassed the 50% national penetration level. So it was an inflection point for the industry, too.

Bodenheimer: I would also add that one of the most famous phrases in cable history was coined by [then Tele-Communications Inc. executive] John Sie that year, or the year prior: That the cable industry needed “punch through” programming. The NFL, in '87, was the epitome of punch-through programming. So not only was it a success for ESPN, but it was a huge success for the cable industry overall. And really, ESPN went from teenager to young adult that night of the first game.

MCN: Some of your predecessors — Bill Grimes and Roger Werner, for instance — ran the company at a time when it seemed that things were more collegial with the cable industry.

Bodenheimer: It has changed, of course, but I'm an optimist. And having grown up on the cable side of the business, I have an awful lot of relationships in the affiliate world. And [president of Disney and ESPN Networks affiliate sales] Sean Bratches, who succeeded me in that role, is doing more than I ever did now in that world, in terms of the number of products and how hard he and his staff are working.

So in that regard, I think that while, yes it's changed, and yes it gets a little bit more contentious, and yes the stakes get a little higher with consolidation, that at its base level it's about delivering value, and we think ESPN delivers more value than any other basic cable network. We've been saying that for 10 years, and no one has ever disputed that.

MCN: Despite some high-profile standoffs with distributors, it has been unusual for any national network to be off the air for a prolonged period of time.

Bodenheimer: Yes, I think so. I think the bottom line that keeps everybody in check is that there's a mutual need. Content providers certainly need distribution vehicles, and distribution vehicles certainly need good content — now more than ever, as their world becomes much more competitive. So when you get past the rhetoric and the intramural squabble that comes up now and then, at the end of the day mutual need is an important factor. And I don't see that changing.

MCN: In your very public confrontation with Cox Communications Inc. over license fees, there were a lot of efforts on both sides to educate the public. Does the average viewer even understand the relationship between cable networks and local cable companies?

Bodenheimer: I think the average subscriber understands very little of the business positions of these media companies, and doesn't care, nor should they care. They're paying a fee for quality entertainment, and that's really as much as they want to know. When these fights go public, and you have to try to articulate all your business rationale, the consumer just doesn't care. They just want to know what time the game is on. And what channel.

MCN: Every so often, somebody predicts professional sports leagues ultimately will bypass TV networks like ESPN altogether and build affiliations directly with distributors. The way the NFL did with the NFL Network. How do networks continue to add value between the originator of an event — the league — and the viewer who watches it?

Bodenheimer: I think it comes down to a matter of focus and what your primary focus is. A league's focus is to field teams, deal with the players, increase asset value for the owners and market a product. At television networks, our primary goal is to aggregate content and produce it in an entertaining fashion for fans. And those are two very different objectives.

I think that over 25 years, ESPN has demonstrated that it does an excellent job of producing high-quality entertainment for sports fans. And I think that, at that level, leagues are very cognizant of the value that ESPN brings to serving their fans. We're on it 24/7, 365 days a year in every medium. And we will continue to play that role. So, I think that there will be a very vibrant business in the television network business going forward. Cable has a particularly bright future.

MCN: What about ESPN from a cultural standpoint? Has ESPN changed the way we perceive sports and athletes?

Bodenheimer: ESPN certainly has been a factor in growing this giant category we call sports in the U.S. Whether it be the culture of sports heroes, or the highlight culture, or any number of ways you want to look at it. Certainly ESPN has had a cultural influence in that world. Remember, when we launched ESPN, everybody was skeptical that there was even a need for one 24-hour a day channel, much less the six that we have going domestically, as well as the competitors that are also doing the same thing.

So, the sports culture has certainly grown over the last 25 years; that's an understatement. I'll leave it up to you to decide what ESPN's role in that was or wasn't. But certainly you can't look back on the last 25 years and conclude that ESPN wasn't a factor.

MCN: Of course, you remember as a kid, getting your highlights fix for football only during halftimes of Monday Night Football.

Bodenheimer: Sure. Anybody growing up watching knows that era of Monday Night Football — specifically with Howard Cosell doing the halftime — that was where we got our highlights.

Six minutes on Monday night at 10:20. That was it. You lived for it. But now, highlights are available in many places, and people expect to see them.

MCN: Twenty-five years from now, what are going to be the big changes that your successor will be talking about?

Bodenheimer: I think probably just advancement in new technology. Just look at the first 25: If you were asking that question on day one of ESPN history, you'd basically be touting this new notion of cable television. Twenty-five years later, what's the number? Ninety percent of Americans get their television through either cable or satellite delivery. We're in high-definition television, there's 150-plus channels, the Internet is a viable entertainment source. That's just the past 25 years. Generally, technology evolves ever more quickly. I'm just trying to figure out next Tuesday, much less 25 years from now, but I do know that advanced technology will clearly play a role in what ESPN is or becomes then.

MCN: Will we still be hearing the signature six-note musical theme of “SportsCenter?”

Bodenheimer: Gee, I hope so. Whether you're at a commencement address or an airport or in a sports bar. People seem to like that jingle very much. It's become a big part of ESPN.

Media, Math and Myth blogger Stewart Schley writes about media, telecommunications and the business of sports from Denver. He is currently writing a book about the transformation of the U.S. cable television industry.