Who’s Watching Whom?

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

WASHINGTON — What exactly, are the rules for Internet privacy, and who has the right to enforce them?

Those two issues are at the heart of one of the most contentious debates roiling the broadband industry today. The Federal Communications Commission’s reclassification of Internet access as a common-carrier service under Title II of the Communications Act gives the agency new powers to create rules for “protecting” broadband customer proprietary network information (CPNI).

That new authority could lead to creating “opt-in” methods for collecting online personal information that many public-interest groups have been clamoring for, and could take a bite out of targeted behavioral advertising. It is unclear just how the FCC will approach its self-given power to regulate in the space, which is the main dissenting issue that Internet-service providers have with much of the Title II order.

The new broadband CPNI oversight has also created a jurisdictional tug-of-war between the FCC and the Federal Trade Commission, which has been overseeing broadband privacy but must relinquish those duties to the agency under the new rules, unless Congress steps in.

“To have the FCC usurp the authority of the Federal Trade Commission is a very bad idea,” Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), the House Judiciary Committee chairman, told C-SPAN in an interview. “It’s going to lead to regulation of the Internet in ways that some of the people who have been calling for that have not imagined.”

UNCERTAINTY BREEDS WORRY

The fear of the FCC’s regulation of broadband privacy is similar to industry fears about the Internet conduct standard contained in the new Open Internet rules, which is fear of the unknown.

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

The FCC tried to give Internet-service providers some guidance in an Enforcement Bureau advisory issued May 20, but that guidance was essentially a call for ISPs to make good-faith efforts to protect privacy (and if you are unsure, run it by us and we’ll try to advise you).

That is the sort of “you’ll know it when the FCC sees it” approach that has ISPs taking the agency to court over its Internet conduct standard, a plan to potentially take government action against a broad “catch-all” (the FCC’s term) standard to sweep up conduct not prevented specifically under its bright-line network neutrality rules but that could “harm internet openness.”

Among the Title II provisions the FCC decided to impose were the customer-privacy provisions in Section 222 of the Communications Act of 1934.

“Section 222 makes private a customer’s communications network information — i.e. with whom they communicate and from where they communicate — unless a user provides express consent for its commercial use,” said Scott Cleland, chairman of NetCompetition, a pro-competition online forum supported by broadband interests, who added that the FCC has some “big decisions” to make. (See sidebar)

The FCC opted to forbear, or choose not to apply, the specific telephone-centric language of the section, preferring to come up with some new definitions for broadband CPNI protection. Just what those new definitions are and what they might cover is at the heart of the debate.

TURF WAR

In pushing to retain jurisdiction over online data security, Jessica Rich, director of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, told Congress at a March hearing that the FCC’s decision to reclassify ISPs under Title II, which removes the issue from FTC purview, had made it harder to protect consumers.

A bill that passed out of the House Energy & Commerce Committee would move some of the CPNI authority the FCC has just given itself back to the Federal Trade Commission by giving the latter agency authority over data privacy when that privacy has been violated due to a breach. The bill would make not protecting personal information per se false and deceptive, empowering the FTC to sue any company — including a cable operator or telecom carrier — that fails to do so. The measure says companies must “implement and maintain reasonable security measures and practices” to protect that information, so the FTC would have to decide what would pass muster.

Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), ranking member of the House Energy & Commerce Committee, has expressed his concern that moving that oversight back to the FTC could be an “enormous problem” because it could allow those ISPs to get out from under FCC privacy oversight through self-regulatory mechanisms at the Federal Trade Commission.

While the FCC has rulemaking authority — and has signaled it could come up with broadband-specific rules — the FTC is limited to using its power to sue companies over false and deceptive conduct.

Under the proposed new legal regime, the FCC and the FTC would share jurisdiction over broadband personal information. The bill gives the FTC cybersecurity and breach oversight, but leaves privacy protections to the FCC, though FCC chief counsel for cybersecurity Clete Johnson has said that is a distinction without a difference.

Johnson told Congress that the way the bill divides up accountability and narrowly defines what information could be protected, the FCC would lose the authority over protecting a subscriber’s viewing-history information, including the shows they watch and the movies they order. At present, what a Congressman watches in Las Vegas stays in Vegas, and under the protection of the ISP there.

“[W]hether a company (either by human error or technical glitch) mistakenly fails to secure customer data or deliberately divulges or uses information in ways that violate a customer’s privacy rights regarding that data, the transgression is at once a privacy violation and a security breach,” he said.

But getting Congress to pass a bill is a tall order, so unless the courts reject the FCC’s Open Internet rules for a second time, the agency is going to be coming up with some form of privacy-protection enforcement regime for broadband information.

CALL FOR HELP

At a panel at last month’s INTX in Chicago, National Cable & Telecommunications Association executive vice president James Assey said that folks trying to comply with the law are looking for help from the FCC as they try to figure out how to comply and get “some assurance” that what they are doing won’t run afoul of the law.

At a meeting of the Advanced Television Systems Committee in Washington, D.C., NCTA president and CEO Michael Powell warned against the government inserting itself into the role data can play in tailoring consumer experiences. He conceded that the use of personal data had troubling elements, but cautioned the government could “distort the market” if it acted prematurely.

The NCTA had no comment on the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau advisory, but it did not weigh in with thanks for the new guidance.

The NCTA and other ISPs outlined their concerns over the Section 222 issue in their May 13 request that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit stay the Title II reclassification and its attendant new broadband CPNI authority.

Telco AT&T estimated it would lose hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues if it had to stop using broadband-related CPNI while it implemented consent mechanisms based on having to “guess” what future FCC rules might be.

While broadband providers can, and do, lawfully use information about customers’ Internet service to develop customized marketing programs, the ISPs said they now can’t be sure what will be acceptable under the new rules and could be held liable if they guess wrong.

The FCC appears to have the votes to flex its muscle on privacy.

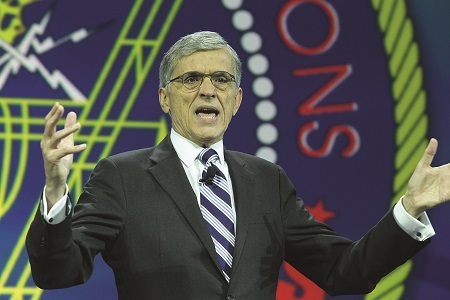

A month ago, the FCC held a workshop essentially launching the process of figuring out what it was going to do with its new privacy authority. FCC chairman Tom Wheeler framed the issue in historical terms, citing the Federalist Papers and intercepted telegraph messages during the Civil War.

“Consumers have the right to expect privacy in the information networks collect about them,” he said, adding that a in digital world, everybody is leaving digital footprints “all over the place.”

Privacy is unassailable, as the virtuous circle of innovation begetting innovation essential, he said.

Wheeler clearly views privacy — like competition and access — as one of those issues that must be viewed in the sweep of history and with the long view from the high hill. That could make it difficult for opponents of strong new FCC privacy regulations to dissuade him from that course with an argument that lies in the weeds of policy.

That’s the same view that helped move his position toward Title II in the first place.

At INTX, Democratic FCC member Jessica Rosenworcel signaled that there were a number of areas where the agency needed to be looking, including monetization of customer data and ad analytics. She said it would be important to align those obligations with the FCC’s traditional cable privacy oversight and suggested the agency needed to have a rulemaking — and that the chairman had acknowledged as much — because it was an area “where time and technology have made really significant changes and we are going to have to figure out how to protect consumer privacy and manage all those benefits from the broadband ecosystem at the same time.”

“You can dial a call, write an email, post an update on a social network and purchase something online, and you can be sure that there are specialists in advertising and data analytics who are interested in exactly where you are going and what you’re doing,” she said. “And then, finally, we all know that the monetization of data is big businesses, and that slicing and dicing is only going to continue.”

Commissioner Mignon Clyburn has said the public demands a “regulatory backstop” on broadband privacy and she is ready to use that power.

SKEPTICAL GOP

The FCC’s Republican minority is hardly convinced — but they are the minority.

Commissioner Ajit Pai told cable operators at INTX that one thing he gleaned from the FCC’s privacy workshop was that nobody really knows where the agency goes from here.

Commissioner Michael O’Rielly told an INTX crowd that the FCC’s understanding of privacy was “prehistoric” and “to now say that we are going to jump in the middle of this space is extremely problematic.” As to the impact on monetizing data, he pointed out that was why a lot of Internet content was free.

Privacy advocates definitely see a chance to push for tough privacy provisions.

Jeff Chester, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Digital Democracy and a leading advocate for online privacy law and regulation, said the FCC has “long looked the other way as phone and cable companies, with their broadband partners, secretly grabbed customer data so they could do more precise set-top box and cross-device tracking and targeting.”

The FCC needs to use its new powers under Title II to force privacy protection on broadband giants, he said. But the FCC should also look at how “Google, Facebook and other data technology companies work alongside the Verizons and Comcasts, in order to develop effective safeguards for the public,” he added, suggesting his own sweeping change.

“The FCC should issue a new ‘Bill of Consumer Rights’ for the digital video era,” Chester said.

The public still has a strong expectation of privacy, said Harold Feld, senior vice president of Washington, D.C.-based public-interest group Public Knowledge. That point was supported by a recent Pew Research study that found that more than 90% of respondents said it was important for them to control who can access information about them online and what information is being collected.

Feld told the FCC at its privacy workshop that “rock solid” phone-network privacy protections need to move into the IP-delivered world. “This is not about, ‘Well, the universe is an awful place for privacy, so who cares anymore.’ ”

Clearly the FCC cares, but until it weighs in with a new regime — and starting June 12, unless the Title II reclassification is stayed by the courts — ISPs will have to trust their gut and likely verify with the FCC as well.

Privacy’s Big Three

If the Federal Communications Commission’s reclassification of broadband as a Title II telephone service is not stayed in court, the ISP industry’s business model could be dramatically affected by how the agency implements Section 222 “Privacy of Customer Information.”

Section 222 makes private a customer’s communications network information, i.e., with whom they communicate and from where they communicate — unless a user provides express consent for its commercial use.

The FCC has some big and telling decisions to make:

Privacy Protection Predictability: Does the FCC believe in a consumer-centric implementation of Section 222, where consumers enjoy privacy protection predictability because the FCC interprets that consumers own or legally control their Section 222 private-network information, and that anyone who wants to commercialize it, must first get the consumer’s express consent? If not, can everyone but an ISP use this legally private Section 222 information in any way they want, whenever they want for most any commercial purpose they want, without notifying or securing the affected consumer’s consent?

Competitive Privacy Policy Parity: Does the FCC want to promote competition, consumer choice and a level playing field by ensuring that all competitors compete based on the same consumer privacy protection rules? If not, will the FCC pick market winners and losers by allowing only FCC-favored competitors to earn revenues in targeted advertising?

FCC Do Not Track List: Will the FCC create a Section 222 Internet “Do Not Track” list like the FTC created the “Do Not Call” list enjoyed by three-quarters of Americans? Why would it not be in the public interest for the FCC to use Section 222 to make available a similarly simple and convenient mechanism for Americans to choose to opt out of unsolicited tracking of where they go on the Internet via a national FCC Do Not Track list that would protect consumers’ private information from commercialization without permission?

In short, how the FCC implements its newly asserted Section 222 “Privacy of Customer Information” authority will speak volumes about the FCC’s true priorities. Will the FCC choose to protect consumers’ privacy interests, or Silicon Valley’s advertising interests?

Scott Cleland is chairman of NetCompetition.org, an e-forum promoting broadband competition and backed by broadband providers.

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.